Are You Up-to-Date on ADA and Wellness Programs Compliance? – EEOC’s Final Rule on Employer Wellness Programs and the Americans with Disabilities Act

Summary

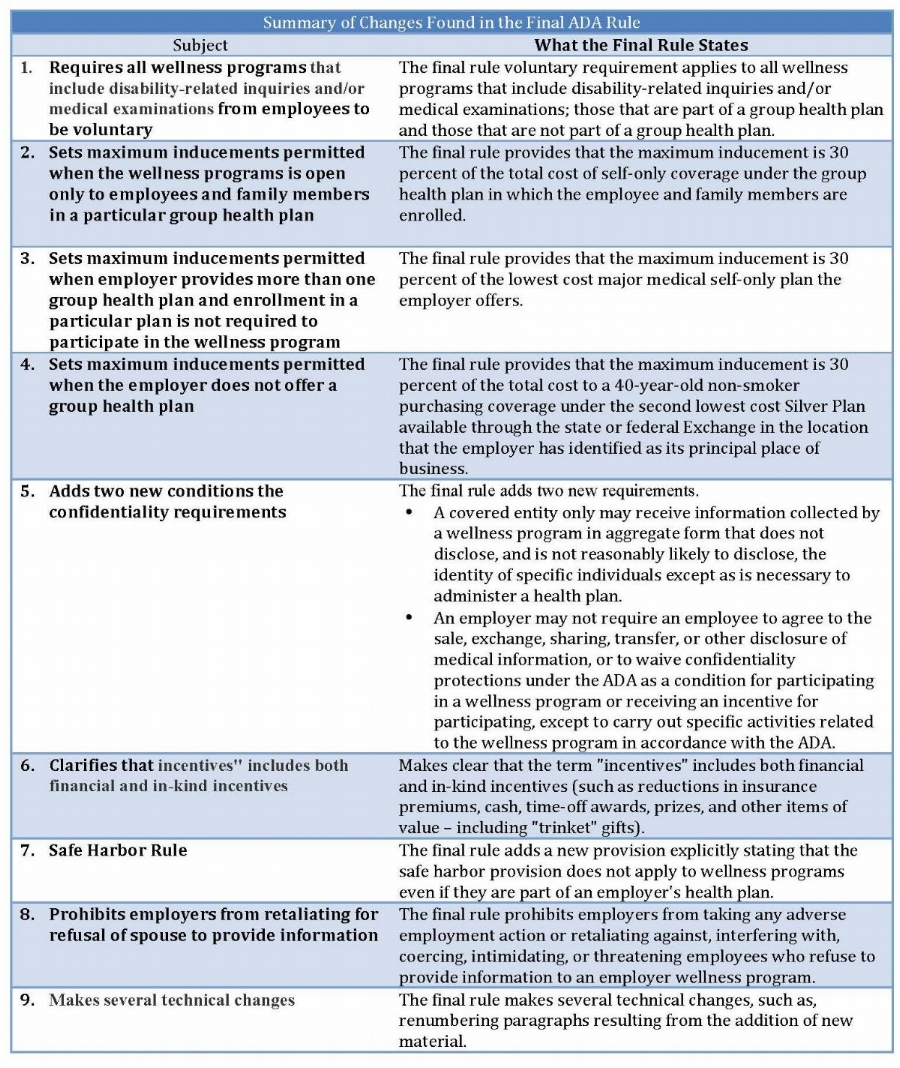

On May 17, 2016, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC or Commission) issued the final rule to amend Title I of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and the accompanying Interpretive Guidance (also known as the Appendix) implementing Title I of the ADA as they relate to employer wellness programs. The final rule provides, among other things, that employers may provide limited financial and other inducements or incentives in exchange for an employee answering disability-related questions or taking medical examinations as part of a wellness program, whether or not the program is part of a health plan.

EEOC, in this final rule setout to accomplish several things: (1) provide guidance on the degree to which an employer may offer inducements or incentives to employees to participate in wellness programs that asked disability-related questions, or required the employee to undergo medical examinations, (2) to provide consistency with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) rules on wellness program incentives; (3) to ensure that incentives would not be of a compelling amount, such that they acted as an economic coercion rendering providing medical information involuntary; and (4) to provide clarity on the difference between the ADA’s requirements for voluntary health programs and other federal laws governs wellness programs that are part of a group health plan, such as the HIPAA as amended by the ACA.

Effective Date and Application Date

The final rule was effective on July 18, 2016. The new provisions of the final rule concerning the requirement to provide a notice that clearly explains to employees what medical information will be obtained and how it will be used and the limits on incentives apply prospectively. Wellness program compliance will be required on the first day of the first wellness plan year that begins on or after January 1, 2017. . If the health plan that is used to calculate the permissible inducement limit begins on January 1, 2017, January 1, 2017 is the date that the wellness program begins. If the health plan used to calculate the maximum level of inducements begins on April 1, 2017, April 1, 2017 is the date that the wellness program begins. January 1, 2017, and April 1, 2017, respectively, are the dates the new provisions related to incentives and notice requirements apply to the employer-sponsored wellness program. The remaining provisions of the rule that merely clarify existing obligations retain the original application dates. Provisions that clarify apply before and after the effective date of the final rule.

About Title I of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)

Title I of the ADA is a federal civil rights law that prohibits an employer from discriminating against an individual with a disability in connection with, among other things, employee compensation and benefits. Title I of the ADA also generally restricts employers from obtaining medical information from applicants and employees. Additionally, Title I of the ADA prohibits employers from denying employees access to wellness programs on the basis of disability, and requires employers to provide reasonable accommodations (adjustments or modifications) that allow employees with disabilities to participate in wellness programs and to keep any medical information gathered as part of the wellness program confidential. The ADA does not however prohibit employers from inquiring about employees’ health or doing medical examinations as part of a voluntary employee health program, as defined by the ADA.

Examples of Legal Challenges Under the ADA

A wellness program may be legally challenged under the ADA, if the program adversely affects “disabled” employees by withholding discounts or denying reimbursements for failure to participate in a program. An example, when an employer has a walking program that results in an award that could be defined as “employee compensation.” If someone with a disability cannot participate in the walking program, the employer may be held to have violated the ADA, unless the wellness program provides alternatives for disabled employees to earn the additional compensation as well.

Another example is that if a wellness program requirement (such as achieving a particular blood pressure or glucose level or body mass index) disproportionately affects individuals on the basis of some protected characteristic. The employer may find itself responding to a disparate impact claim if achieving a particular goal is more challenging for those in a particular protected class. For example, women generally carry a higher percentage of fat than men, which would make it more difficult for them to achieve the same BMI. An employer may be able to avoid a disparate impact claim by offering and providing a reasonable alternative standard (i.e. adjust the BMI standard to consider each sex).

Applicability

As stated above, the final rule requires all wellness programs that include disability-related inquiries and/or medical examinations to be voluntary and comply with incentive limitations. These requirements apply to those wellness programs that are part of a group health plan and those that are not part of a group health plan. It applies even if the employer does not offer a group health plan.

As found in the proposed rule, the final rule separates smoking cessation programs into two categories: those that require employees to be tested for nicotine use and those that simply ask employees whether they smoke. A wellness program that only asks employees if they smoke or if they have stopped smoking at the end of the program is not considered to be a wellness program that asks disability-related questions. As such, the ADA does not apply. Nor does the ADA apply to wellness programs that just require employees to engage in activities that do not require employees to answer disability related questions or to undergo medical examinations to earn a reward or avoid a penalty. Having said that, one should keep in mind that notwithstanding the fact that incentive limitations of the ADA do not apply where disability questions are not asked or examinations not required, the ADA does require employers to provide reasonable accommodations that allow employees with disabilities to participate in the wellness programs.

Scenario #1

The employer offers a wellness program as part of a group health plan that simply asks an employee if he or she smokes.

ADA does not apply, because simply asking the questions whether one smokes is not asking a disability related question.

The employer must still however comply with HIPAA, as amended by the ACA; the employer must not offer incentives greater than the 50% percent of the total cost of the health coverage tier in which the employee is enrolled for tobacco-related wellness programs.

Scenario #2

The employer offers a wellness program that is not part of a group health plan that simply as an employee if he or she smokes.

ADA does not apply, because simply asking the questions whether one smokes is not asking a disability related question.

HIPAA does not apply because the program is not connected with a group health plan.

Scenario #3

The employer, as part of a wellness program connected to a group health plan, requires biometric screening or other medical procedure that tests for the presence of nicotine or tobacco.

ADA applies, because of the biometric screening the wellness program is requiring the employee to undergo a “medical examination.” The employer must not offer incentives greater than the 30% threshold based upon self-only coverage.

What’s New in the Final Rule?

Wellness Program Must be Design to Promote Health and Wellness

As stated in the proposed rule, if an employer offers health program that includes any disability-related inquiries and/or medical examinations that are part of such a program, the program must be “reasonably designed to promote health or prevent disease.” To meet this standard, the wellness program must have a reasonable chance of improving the health of the participant or preventing disease in the participant. The program cannot be overly burdensome to employees, or a subterfuge for violating ADA or other employment discrimination laws; nor can the program require employees to incur significant costs for medical examinations.

Examples of a wellness program considered to be reasonably designed to promote health or prevent disease:

- A wellness program that asks employees to answer questions about the employees’ health conditions or have a biometric screening or other medical examination for the purpose of alerting them to health risks (such as having high cholesterol or elevated blood pressure)

- Collecting and using aggregate information from employee HRAs to design and offer programs aimed at specific conditions prevalent in the workplace (such as diabetes or hypertension).

A wellness program is not considered to be reasonably designed to promote health or prevent disease if:

- It asks for employees to provide medical information on a HRA without providing any feedback about risk factors or without using aggregate information to design programs or treat any specific conditions.

- It exists merely to shift costs from an employer to employees based on their health;

- Is used by the employer only to predict its future health costs; or

- Imposes unreasonably intrusive procedures, an overly burdensome amount of time for participation, or significant costs related to medical exams on employees.

Participation Must be Voluntary

As stated in the proposed rule, the final rule lists several requirements necessary for an employee’s participation in a wellness program that includes disability-related inquiries or medical examinations to meet the definition of “voluntary”. An employer:

- May not require any employee to participate;

- May not deny any employee who does not participate in a wellness program access to health coverage or prohibit any employee from choosing a particular plan;

- May not take any other adverse action or retaliate against, interfere with, coerce, intimidate, or threaten any employee who chooses not to participate in a wellness program or fails to achieve certain health outcomes.

- Must provide a notice that is written so that the employee from whom medical information is being obtained is reasonably likely to understand it; that describes the type of medical information that will be obtained and the specific purposes for which the medical information will be used; and that clearly explains restrictions on the disclosure of the employee’s medical information, the employer representatives or other parties with whom the information will be shared, and the methods that the covered entity will use to ensure that medical information is not improperly disclosed (including whether it complies with the measures set forth in the HIPAA regulations).

- Must comply with the incentive limits discussed below as it relates to the wellness program.

Inducements Limits[1]

If a wellness program is open only to employees and family members in a particular group health plan, then the maximum inducement is 30 percent of the total cost of self-only coverage[2] under the group health plan in which the employee and family members are enrolled.

Example: if an employee is enrolled in a self and family plan for a total premium of $14,000 (employee plus employer contribution), and the health plan has a self-only option for a total cost of $6,000, the maximum inducement is 30% of $6,000, which equals $1,800.

If an employer provides more than one group health plan and the enrollment in a particular plan is not required to participate in the wellness program, the maximum inducement is 30 percent of the lowest cost major medical self-only plan the employer offers.

Example: if an employer has three self-only major medical plans that range in total cost from $5,000 to $8,000, the maximum inducement is 30% of $5,000, which equals $1,500.

If the employer does not offer a group health plan, then the maximum inducement is 30 percent of the total cost to a 40-year-old non-smoker purchasing coverage under the second lowest cost Silver Plan[3] available through the state or federal Exchange in the location that the employer has identified as its principal place of business.

Example: if a 40-year-old non-smoker could purchase the second lowest cost Silver Plan on the State Exchange for $4,000, the maximum inducement is 30% of $4,000, which is $1,200.

Confidentiality Required

The language in the proposed rules about confidentiality, and the exceptions remain in the final rule. The final rule also adds two new requirements:

- A covered entity only may receive information collected by a wellness program in aggregate form that does not disclose, and is not reasonably likely to disclose, the identity of specific individuals except as is necessary to administer a health plan.

- An employer may not require an employee to agree to the sale, exchange, sharing, transfer, or other disclosure of medical information, or to waive confidentiality protections under the ADA as a condition for participating in a wellness program or receiving an incentive for participating, except to carry out specific activities related to the wellness program in accordance with the ADA.

Keep in mind that there are other federal and state laws that protect the confidentiality of medical information obtained through a wellness program. For example, if a wellness program is part of a group health plan, HIPAA’s privacy, security, and breach notification apply. State privacy and security laws, and medical record laws may also apply.

Safe Harbor Does Not Apply

The final rule adds a new provision explicitly stating that the safe harbor provision does not apply to wellness programs even if they are part of an employer’s health plan. The safe harbor provision of the ADA applies when information collected is being used to determine if employees with certain health conditions are insurable or to set insurance premiums. Since, employers collecting information as part of a wellness program are not collecting or using information for this purpose, the ADA safe harbor provision does not apply to employer wellness programs.

Retaliation Prohibited

The final rule prohibits employers from taking any adverse employment action or retaliating against, interfering with, coercing, intimidating, or threatening employees who refuse to provide information to an employer wellness program.

Technical Changes Made

The final rule makes several technical changes, such as, renumbering paragraphs resulting from the addition of new material.

ADA and Other Federal Laws

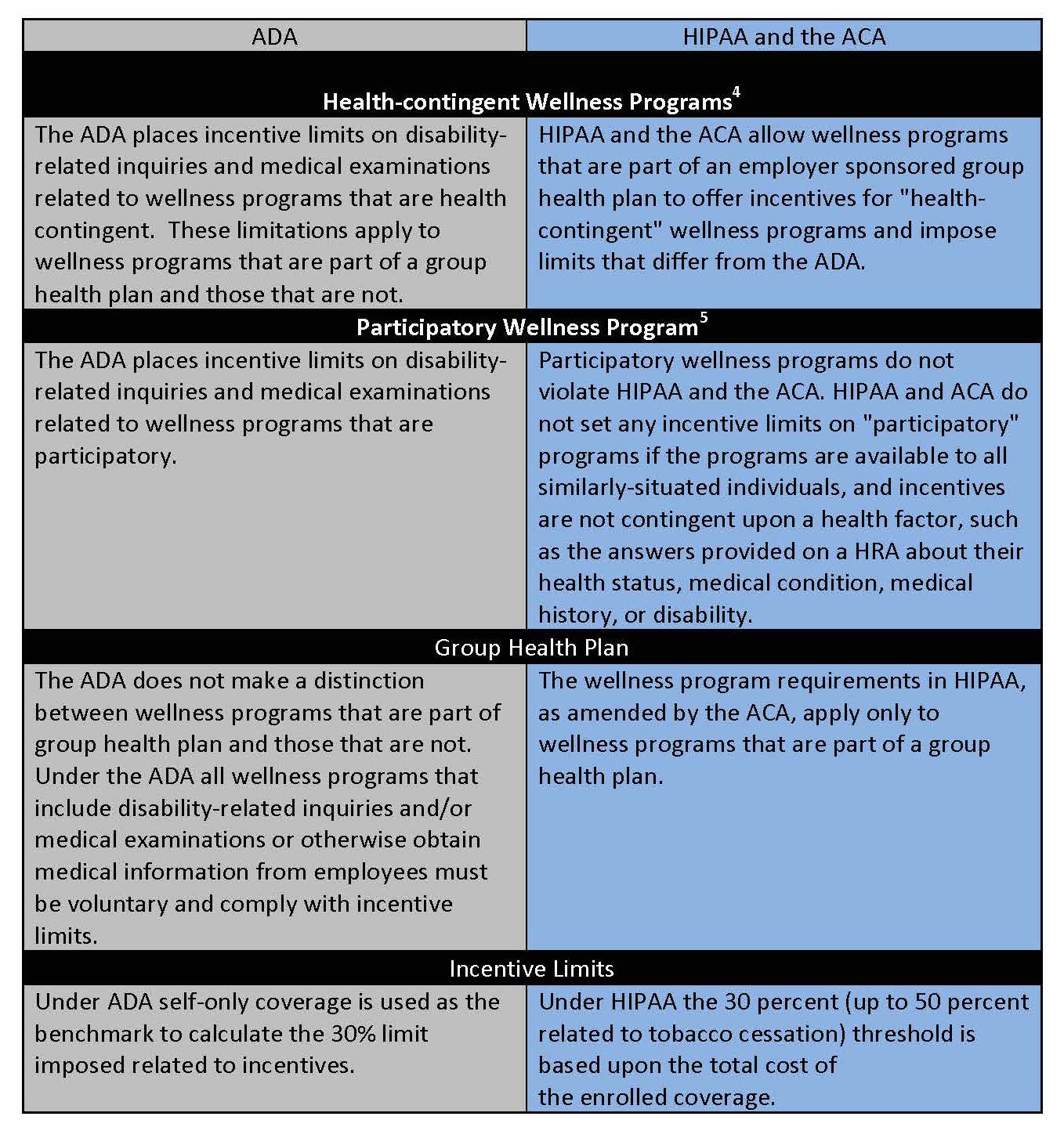

There are some differences between the wellness program rules of the ADA final rule and the wellness program rules under HIPAA and the ACA. There are also aspects of wellness programs that the ADA regulates and that HIPAA and the ACA do not even address.

The wellness program requirements in HIPAA, as amended by the ACA, apply only to wellness programs that are part of a group health plan. And as such, HIPAA and ACA do not address wellness programs that are not part of a group health plan. HIPAA sets limits for incentives offered under a health-contingent wellness program to 30 percent of the total cost of enrolled coverage (and up to 50 percent related to tobacco cessation). HIPAA and the ACA do not however impose a limit on the incentives for participatory wellness programs.

Unlike HIPAA and ACA, the final ADA rule applies to all employer-sponsored wellness programs that require medical examinations or make disability-related inquiries regardless as to whether the program is connected to a health plan, or whether it meets the definition of participatory or health contingent under HIPAA.

The final rules under the ADA (and GINA) do not match with HIPAA’s incentive limits. The EEOC refused to apply the 30 percent threshold based upon the total cost of the enrolled coverage, as in HIPAA. The EEOC reasoned that because the ADA prohibits only discrimination against employees and applicants, and not their spouses and dependents, the self-only coverage was the appropriate benchmark.

FOOTNOTES

[1] All of the inducement limits are exactly the same as the limits on incentives available to employees under Title II of the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA), published at the same time as the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

[2] This is the incentive limit under HIPAA regulations that applies to health-contingent wellness programs that require employees to perform an activity or achieve certain health outcomes.

[3] The Silver Plan is the most frequently purchased plan on the Exchanges.

[4] Health-contingent wellness programs require participants to satisfy a standard related to a health factor in order to obtain a reward. There are two types of health-contingent wellness programs: activity-only and outcome-based.

[5] Participatory wellness programs either do not provide a reward or do not include any conditions for obtaining a reward based on the participant satisfying a standard related to a health factor, such as, programs that only ask employees to complete a Health Risk Assessment.